The Incredible History of Serengeti National Park

The Incredible History of Serengeti National Park

The history of Serengeti National Park spans millions of years of geological evolution, thousands of years of human habitation, and decades of pioneering conservation efforts that transformed this legendary landscape into one of the world’s most celebrated protected areas. Understanding the history of Serengeti National Park reveals not just the story of a single park, but the evolution of wildlife conservation philosophy itself, from exclusive hunting reserves through groundbreaking ecosystem protection approaches that influenced conservation worldwide.

Table of Contents

Serengeti National Park’s history reflects the complex intersections of indigenous peoples’ traditional lands, colonial ambitions, hunting culture, emerging conservation science, and the gradual recognition that preserving intact ecosystems serves humanity’s broader interests. The park’s establishment in 1951 marked the beginning of modern Tanzania’s conservation legacy, though the history of Serengeti extends far deeper into both geological time and human cultural heritage.

Today, when visitors witness the Great Migration’s spectacular river crossings or observe lions resting beneath acacia trees, they experience landscapes shaped by millions of years of natural processes and centuries of human interaction. The history of Serengeti National Park demonstrates how this precious ecosystem survived colonial exploitation, evolved through changing conservation philosophies, and emerged as a UNESCO World Heritage Site representing humanity’s commitment to preserving Earth’s natural heritage.

Safari Stride’s deep understanding of Serengeti’s history enriches our clients’ experiences by providing cultural and historical context that transforms wildlife viewing into comprehensive appreciation of this legendary landscape’s significance. Our expertise helps travelers understand not just what they see in Serengeti today, but the remarkable journey that preserved these ecosystems for future generations.

Geological Origins and Ancient History

The geological history of Serengeti National Park extends back millions of years through dramatic tectonic processes, volcanic activity, and climate changes that shaped the modern landscape supporting today’s spectacular wildlife populations. Understanding this deep history provides foundation for appreciating how the Serengeti ecosystem developed its unique character.

The formation of the East African Rift System approximately 20 million years ago created the geological foundation for the Serengeti ecosystem, with tectonic forces uplifting surrounding highlands while leaving the Serengeti plains at lower elevations. These processes created the topographical features that influence modern rainfall patterns, water flows, and the grassland-woodland mosaics characterizing today’s landscape.

Volcanic activity from nearby volcanic mountains including Ngorongoro, Kerimasi, and Olmoti deposited nutrient-rich ash across the Serengeti plains over millions of years, creating the fertile soils supporting the short grass prairies that attract massive wildebeest herds during calving season. This volcanic legacy remains fundamental to understanding why particular areas support different vegetation types and wildlife concentrations.

Climate fluctuations throughout the Pleistocene epoch dramatically affected the history of Serengeti’s ecosystems, with ice age periods creating cooler, drier conditions alternating with warmer, wetter interglacial periods. These climate oscillations influenced vegetation patterns, wildlife distributions, and the evolutionary adaptations of species that would eventually participate in the Great Migration phenomenon.

The evolution of grassland ecosystems in the Serengeti region occurred relatively recently in geological terms, with extensive grasslands developing only within the last few million years as climate patterns shifted toward drier conditions. This grassland expansion created ideal conditions for large grazing mammal populations that became the Serengeti’s defining characteristic.

Archaeological evidence from Olduvai Gorge in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area bordering Serengeti reveals human presence in the broader ecosystem dating back over 2 million years, with early hominids including Homo habilis and later species leaving tool-making evidence throughout the region. This ancient human history demonstrates that humans and wildlife coexisted in the Serengeti landscape since humanity’s earliest origins.

Fossil records from the Serengeti region document the evolution of African wildlife over millions of years, with ancestors of modern elephants, giraffes, and various antelope species leaving evidence of gradual evolutionary changes responding to shifting environmental conditions. This paleontological record helps scientists understand how today’s wildlife communities developed their specialized adaptations.

Indigenous Peoples and Traditional Land Use

The history of Serengeti National Park includes thousands of years of human habitation by indigenous peoples whose traditional land use practices shaped the landscape encountered by European explorers. Understanding these indigenous histories provides crucial context for appreciating the complex heritage of lands that became protected conservation areas.

The Maasai people’s arrival in the Serengeti region approximately 200-300 years ago brought pastoral traditions that integrated cattle herding with wildlife presence across shared landscapes. The Maasai’s seasonal grazing patterns, cultural practices, and spiritual connections to the land created human-wildlife coexistence models that persisted until colonial interventions altered traditional land use systems.

Earlier inhabitants of the Serengeti region including the Datoga, Hadzabe, and other groups practiced hunting, gathering, and varying degrees of pastoralism that left lighter impacts on wildlife populations compared to later commercial hunting. These indigenous societies developed sophisticated ecological knowledge and sustainable resource use practices based on centuries of accumulated experience in the Serengeti ecosystem.

Traditional ecological knowledge among Serengeti’s indigenous peoples included understanding of wildlife migration patterns, seasonal resource availability, water sources, and vegetation cycles that guided sustainable land use strategies. This knowledge, developed over generations, represented invaluable wisdom about ecosystem function that colonial administrators and early conservationists often dismissed or failed to recognize.

Sacred sites and spiritual connections to the Serengeti landscape held deep cultural significance for indigenous peoples, with particular mountains, rocks, trees, and water sources carrying religious meaning that shaped traditional conservation practices. These spiritual relationships fostered respectful attitudes toward nature that aligned with modern conservation ethics, though through different cultural frameworks.

Seasonal burning practices employed by indigenous peoples influenced vegetation patterns throughout the Serengeti region, with controlled fires clearing old grass, promoting fresh growth, and maintaining the grassland-woodland balance that supported diverse wildlife communities. These traditional fire management approaches inadvertently contributed to ecosystem health, though their role was not understood until much later in the history of Serengeti conservation.

Human population densities in the Serengeti region remained relatively low prior to colonial era, allowing wildlife populations to thrive despite human presence. This demographic pattern reflected both the challenging environmental conditions of semi-arid grasslands and cultural practices that maintained balance between human needs and ecosystem carrying capacity.

Colonial Era and Early Exploration

The colonial period in the history of Serengeti National Park introduced dramatic changes to the region as European explorers, hunters, and administrators arrived with perspectives on wildlife and land use fundamentally different from indigenous traditions. This era laid foundations for both devastating wildlife exploitation and eventual conservation initiatives.

European exploration of the Serengeti region began in earnest during the late 19th century, with explorers including Oscar Baumann and subsequent German colonial expeditions documenting the region’s spectacular wildlife populations. These early accounts described seemingly endless herds of wildebeest, zebras, and other species that captivated European imaginations while triggering commercial hunting interests.

German colonial administration of Tanganyika (mainland Tanzania’s colonial name) from the 1880s until World War I included initial efforts to regulate hunting through license systems, though enforcement remained minimal and commercial hunting decimated some wildlife populations. The Germans recognized the Serengeti’s wildlife significance but prioritized resource extraction over conservation during this period.

The British colonial takeover following World War I brought new administrative approaches to the Serengeti region, with British authorities gradually developing more structured wildlife management policies influenced by emerging conservation ideas from other colonial territories. However, sport hunting remained the dominant paradigm, with wildlife viewed primarily as recreational resources for European hunters.

Trophy hunting culture during the colonial era treated Serengeti wildlife as unlimited resources available for exploitation, with wealthy European and American hunters pursuing the “big five” and other species with minimal restrictions. Hunting safaris became major economic activities, though they contributed to significant wildlife population declines particularly among lions, elephants, and rhinoceros.

The establishment of a partial game reserve in 1921 covering portions of what would become Serengeti National Park represented the first formal protection efforts, though hunting remained permitted and enforcement remained weak. This partial reserve reflected growing awareness that unregulated hunting threatened wildlife populations, though conservation remained subordinate to hunting interests.

Professional hunters and their clients including famous figures like Theodore Roosevelt and Ernest Hemingway visited the Serengeti region during the colonial era, with their hunting exploits and writings publicizing the area’s wildlife abundance to international audiences. These accounts simultaneously celebrated and contributed to wildlife exploitation while gradually fostering conservation sentiment.

The Path to National Park Status

The transformation from partial game reserve to full national park status represents a crucial chapter in the history of Serengeti National Park, involving debates about conservation philosophy, conflicts over land use, and the gradual recognition that comprehensive ecosystem protection served broader interests than hunting reserves.

The 1929 expansion of game reserve boundaries incorporated larger areas of the Serengeti plains, reflecting growing concern about wildlife population declines and increasing recognition of conservation values. However, hunting continued within portions of the expanded reserve, demonstrating that full protection remained controversial even as conservation awareness grew.

World War II’s conclusion in 1945 brought renewed attention to conservation issues across British colonial territories, with post-war idealism including recognition that natural heritage deserved protection. The Serengeti’s spectacular wildlife made it a priority candidate for enhanced protection as British authorities developed more ambitious conservation policies.

The Serengeti Committee formed in 1948 brought together colonial administrators, conservation advocates, and scientific experts to assess the Serengeti region’s conservation needs and recommend appropriate protection measures. This committee’s deliberations reflected emerging understanding that effective conservation required scientific management based on ecological principles rather than simply restricting hunting.

Conflicts between conservation goals and Maasai land rights created major controversies during discussions about national park establishment, as full protection required relocating Maasai communities from their traditional lands. These conflicts highlighted the colonial era’s failure to reconcile conservation with indigenous peoples’ rights, setting patterns that continue affecting conservation-community relationships today.

The official establishment of Serengeti National Park on December 28, 1951 marked a watershed moment in Tanzanian and African conservation history, creating one of the continent’s first major national parks dedicated to comprehensive ecosystem protection. The park initially covered approximately 14,750 square kilometers, encompassing the central and western Serengeti regions.

The exclusion of Ngorongoro highlands from Serengeti National Park in 1959, creating the separate Ngorongoro Conservation Area, resulted from controversies over Maasai displacement and represented a compromise allowing continued Maasai residence and grazing alongside wildlife conservation. This separation addressed some concerns about colonial conservation’s impact on indigenous peoples while maintaining protection for the main Serengeti ecosystem.

Scientific Research and the Grzimek Legacy

Scientific research transformed understanding of the Serengeti ecosystem during the mid-20th century, with pioneering studies establishing ecological knowledge that revolutionized conservation approaches. The history of Serengeti National Park includes remarkable scientific legacies that continue influencing wildlife management today.

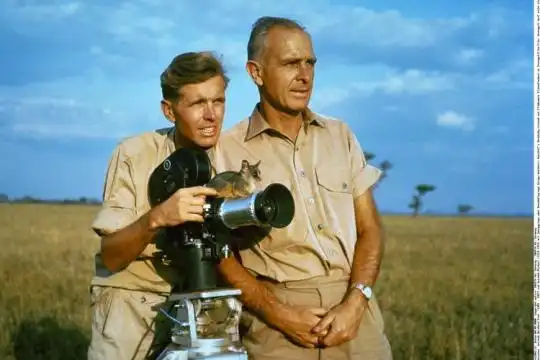

Bernhard and Michael Grzimek’s arrival in Serengeti during the late 1950s marked the beginning of systematic scientific study of the park’s wildlife, particularly the Great Migration. These German zoologists brought rigorous research methods and deep passion for understanding Serengeti’s ecological complexity, producing knowledge that proved crucial for effective conservation.

The tragic death of Michael Grzimek in a plane crash during aerial wildlife surveys in 1959 created a martyr for the conservation cause, with his sacrifice highlighting the dedication required for understanding and protecting wild places. Michael Grzimek was buried in Ngorongoro Crater, creating a memorial that reminds visitors of the personal costs of conservation pioneering.

Bernhard Grzimek’s book “Serengeti Shall Not Die” and accompanying documentary film brought international attention to Serengeti conservation while advocating for comprehensive ecosystem protection. These influential works helped secure funding and political support for Serengeti conservation while educating global audiences about the ecosystem’s spectacular wildlife and conservation needs.

The establishment of the Serengeti Research Institute in 1966 institutionalized scientific research in the park, creating permanent infrastructure for long-term ecological studies. This research station attracted scientists worldwide, generating crucial knowledge about wildlife behavior, population dynamics, predator-prey relationships, and ecosystem processes that informed adaptive management.

Long-term wildlife monitoring programs initiated during the 1960s and continuing today provide invaluable data tracking population trends, migration patterns, and ecological changes over decades. These monitoring efforts represent some of the world’s longest continuous wildlife studies, offering insights into ecosystem dynamics impossible to obtain through short-term research.

Groundbreaking studies of lion behavior and social structure by George Schaller and later researchers revealed complex social dynamics and hunting strategies that revolutionized understanding of apex predators. This lion research established Serengeti as a premier location for predator ecology studies while contributing fundamental knowledge to conservation biology.

The discovery and documentation of the Great Migration’s full annual cycle through systematic research revealed the interconnections between Serengeti plains, western corridor, and northern regions that demonstrated the necessity of protecting entire ecosystems rather than isolated reserves. This migration research proved pivotal in justifying Serengeti’s large protected area boundaries.

Independence and Tanzanian Conservation

Tanzania’s independence in 1961 brought new chapters to the history of Serengeti National Park as the young nation inherited colonial-era conservation areas while developing distinctly Tanzanian approaches to wildlife protection and national park management that continue shaping conservation today.

Julius Nyerere’s leadership of independent Tanzania included strong commitment to conservation, with the founding president declaring that wildlife conservation represented national priorities alongside economic development. Nyerere’s vision positioned conservation as integral to national identity rather than colonial legacy, helping build public support for protected areas.

The Arusha Manifesto of 1961, issued shortly after independence, articulated Tanzania’s conservation philosophy with Nyerere declaring wildlife as held “in trust” for future generations and world heritage. This manifesto established conservation as government policy while framing it within African rather than colonial contexts, representing ideological foundations for Tanzanian conservation.

The establishment of Tanzania National Parks Authority in 1959, just before independence, created institutional frameworks for managing Serengeti and other protected areas under Tanzanian rather than colonial control. This authority gradually developed management capacity, scientific expertise, and administrative systems enabling effective park governance.

The designation of Serengeti as UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981 recognized the park’s “outstanding universal value” while internationalizing conservation responsibilities. This designation brought international prestige, funding opportunities, and global attention that strengthened conservation while acknowledging that Serengeti’s importance transcended national boundaries.

The expansion of Serengeti National Park boundaries over subsequent decades reflected improved ecological understanding and commitment to comprehensive ecosystem protection, with expansions incorporating crucial wildlife corridors and seasonal ranges. These boundary adjustments demonstrated adaptive management responding to scientific knowledge rather than maintaining arbitrary colonial demarcations.

Community conservation initiatives beginning in the 1980s and expanding through subsequent decades represented recognition that conservation success required engaging surrounding communities as partners rather than viewing them as threats. These programs including revenue sharing, employment opportunities, and community wildlife management areas represented evolution beyond colonial-era exclusionary conservation models.

International partnerships and funding from conservation organizations worldwide supported Serengeti conservation efforts as Tanzania’s government welcomed collaborative approaches addressing challenges beyond national capacity. Organizations including Frankfurt Zoological Society, which Bernhard Grzimek founded, maintained long-term commitments to Serengeti conservation alongside numerous other international partners.

Conservation Challenges and Responses

The history of Serengeti National Park includes ongoing struggles against various threats to ecosystem integrity, with each challenge prompting innovative responses that advanced conservation practice. Understanding these challenges and responses reveals conservation as continuous adaptation rather than static achievement.

Poaching crises during the 1970s and 1980s threatened wildlife populations as economic challenges, weak enforcement, and international ivory demand created perfect conditions for illegal hunting. Elephant and rhinoceros populations suffered particularly severe declines, requiring major anti-poaching investments and international cooperation to reverse population crashes.

The development of professional ranger forces equipped with training, vehicles, weapons, and communications equipment represented crucial responses to poaching threats. These anti-poaching units, supported by international funding and technical assistance, gradually reduced illegal hunting while demonstrating that effective enforcement requires substantial resource investments.

Human population growth surrounding Serengeti created increased pressures from habitat conversion, resource use conflicts, and human-wildlife conflicts that continue challenging conservation today. These demographic pressures require sophisticated approaches balancing conservation with human development needs in ways that build rather than erode local support for protected areas.

Tourism development in Serengeti presented both opportunities and challenges, with visitor revenues supporting conservation while tourism infrastructure and activity potentially impacting wildlife and ecosystems. Managing tourism sustainably requires ongoing attention to visitor numbers, infrastructure locations, and activity regulations that balance economic benefits with conservation priorities.

Climate change emerged as a major concern affecting the history of Serengeti National Park’s future trajectory, with shifting rainfall patterns, temperature increases, and vegetation changes potentially disrupting migration patterns and ecosystem dynamics. Responding to climate change requires adaptive management approaches and international cooperation addressing threats beyond any single nation’s control.

Infrastructure threats including proposed roads through Serengeti corridors periodically emerge as development pressures conflict with conservation priorities. Advocacy efforts by conservation organizations, scientists, and concerned citizens successfully defeated some infrastructure proposals while demonstrating the ongoing vigilance required to protect Serengeti from inappropriate development.

Invasive species introductions and disease outbreaks periodically threatened Serengeti wildlife, with canine distemper affecting lions and other diseases potentially transmitted from domestic animals highlighting the interconnections between livestock, wildlife, and human health. These disease challenges require integrated approaches addressing wildlife health, livestock management, and human practices simultaneously.

The Great Migration: Ecological Phenomenon and Conservation Icon

The Great Migration has become inseparable from the history of Serengeti National Park, representing both the ecosystem’s defining natural phenomenon and the most powerful symbol for conservation advocacy. Understanding the migration’s role in Serengeti’s history reveals how spectacular wildlife gatherings inspire conservation commitment.

The discovery by scientists of the Great Migration’s full annual cycle transformed understanding of Serengeti’s ecological importance while demonstrating that effective conservation required protecting entire migration routes rather than isolated areas. This recognition influenced decisions about park boundaries, buffer zones, and transboundary conservation with Kenya’s Maasai Mara.

The annual migration of over two million wildebeest, zebras, and gazelles following seasonal rainfall and grass growth patterns represents one of Earth’s greatest wildlife spectacles, attracting global attention and tourism that economically justifies conservation investments. The migration’s fame has made Serengeti synonymous with African wildlife while generating crucial conservation funding.

Scientific understanding of migration dynamics evolved through decades of research tracking animal movements, documenting population trends, and analyzing the ecological factors driving this extraordinary phenomenon. Research revealed that the migration reflects sophisticated responses to rainfall patterns, grass nutrition, predation risks, and other factors demonstrating remarkable evolutionary adaptations.

According to the Tanzania National Parks Authority, the Great Migration generates substantial tourism revenue that directly supports conservation while demonstrating to Tanzanians the economic value of protecting wildlife. This economic argument has proven crucial for maintaining political support for conservation despite competing development pressures.

The Mara River crossings occurring during the northern migration represent the most dramatic and photographed moments, with thousands of wildebeest braving crocodile-infested waters in spectacular displays of survival instinct. These crossings have become iconic images representing Serengeti while attracting photographers and filmmakers worldwide.

Climate change impacts on migration timing and routes present emerging concerns for the future, with shifting rainfall patterns potentially disrupting the synchronized movements that have characterized the migration for millennia. Monitoring these changes and developing adaptive conservation responses represents crucial challenges for maintaining the migration phenomenon.

Modern Serengeti: 21st Century Conservation

The contemporary era in the history of Serengeti National Park reflects sophisticated conservation approaches integrating scientific research, community engagement, tourism management, and international cooperation while addressing 21st century challenges including climate change, habitat fragmentation, and human population growth.

Technology integration including GPS collaring, camera traps, drone surveillance, and data analytics has revolutionized wildlife monitoring and anti-poaching efforts in Serengeti. These technological tools provide unprecedented insights into animal movements, population dynamics, and threat patterns while improving ranger effectiveness through real-time intelligence.

Community conservation areas surrounding Serengeti including wildlife management areas and controlled grazing zones represent recognition that conservation success requires landscapes beyond park boundaries. These buffer zones attempt to balance wildlife conservation with human land uses while maintaining connectivity between protected areas essential for migration routes.

Tourism infrastructure development continues expanding to meet growing visitor demand while raising questions about appropriate development levels and sustainable tourism practices. Managing this growth requires balancing economic opportunities against potential negative impacts on wildlife and visitor experiences, ongoing challenges without simple solutions.

Scientific research continues advancing understanding of Serengeti’s complex ecosystems through studies examining climate change impacts, disease dynamics, human-wildlife conflicts, and numerous other topics. The Serengeti ecosystem represents one of the world’s most studied wildlife systems, generating knowledge benefiting conservation worldwide.

International partnerships including UNESCO World Heritage designation, transboundary conservation cooperation with Kenya, and funding from global conservation organizations maintain Serengeti as a priority for international conservation community. These partnerships provide crucial resources and expertise while recognizing that Serengeti’s importance transcends national boundaries.

Education and outreach programs engaging Tanzanian students, communities, and citizens in conservation build domestic support for Serengeti protection. These educational initiatives recognize that long-term conservation success requires Tanzanians valuing wildlife as national heritage rather than viewing conservation as external imposition.

Cultural Significance and Global Legacy

The history of Serengeti National Park extends beyond conservation achievements to encompass cultural significance and global influence that made Serengeti synonymous with African wilderness while inspiring conservation movements worldwide.

Serengeti’s prominence in nature documentaries beginning with the Grzimeks’ work and continuing through countless subsequent films has shaped global perceptions of African wildlife. Documentaries from the BBC’s “Planet Earth” series to National Geographic specials have made Serengeti landscapes and wildlife familiar to millions who may never visit, building broad conservation constituencies.

The park’s influence on conservation philosophy worldwide includes demonstrating that ecosystem-scale protection produces superior conservation outcomes compared to small isolated reserves. The Serengeti model influenced protected area planning globally while establishing principles now considered fundamental to conservation biology.

Cultural representations in literature, art, photography, and film have made Serengeti iconic in ways transcending its physical boundaries. The park appears in countless books, from serious conservation literature to children’s stories, creating cultural associations that embed Serengeti in global consciousness.

Tourism’s economic impacts extend far beyond park boundaries, supporting regional economies through employment, business opportunities, and infrastructure development. The Serengeti tourism industry demonstrates how conservation generates tangible economic benefits, providing crucial arguments for continued protection.

The park serves as inspiration for conservation advocates worldwide, with Serengeti’s survival despite numerous threats demonstrating that dedicated conservation efforts can succeed. This inspirational value mobilizes support for conservation initiatives globally while providing hope that other threatened ecosystems can be saved.

Indigenous rights discussions continue evolving as descendants of displaced Maasai communities maintain cultural connections to Serengeti lands while conservation models attempt reconciling protection with indigenous peoples’ rights. These ongoing dialogues reflect unresolved tensions in the history of Serengeti National Park while indicating potential paths toward more inclusive conservation.

Conclusion: Lessons from Serengeti’s History

The history of Serengeti National Park demonstrates that conservation success requires long-term commitment, adaptive management, scientific foundations, community engagement, and international cooperation. The park’s survival through colonial exploitation, poaching crises, development pressures, and countless other challenges reveals conservation as continuous effort rather than permanent achievement.

Understanding Serengeti’s history enriches visitor experiences by providing context for the landscapes and wildlife they witness, revealing the remarkable journey that preserved these ecosystems through multiple existential threats. Every wildlife sighting in today’s Serengeti reflects decades of conservation dedication by countless individuals from Bernhard Grzimek through contemporary rangers risking their lives protecting wildlife.

The lessons from the history of Serengeti National Park extend far beyond Tanzania’s borders, informing conservation approaches worldwide while demonstrating that spectacular wildlife populations can recover when given protection and proper management. Serengeti stands as proof that conservation investments generate returns through ecosystem services, tourism revenue, and intrinsic values that justify the costs.

Future challenges including climate change, human population growth, and evolving threats will test whether the conservation successes chronicled in the history of Serengeti National Park can be sustained. However, the ecosystem’s resilience demonstrated throughout its history provides hope that with continued commitment, Serengeti will endure for future generations.

Safari Stride’s deep appreciation for Serengeti’s history informs our guiding philosophy and client experiences, ensuring visitors understand not just the spectacular wildlife they witness but the remarkable conservation legacy that preserved these wonders. Our expertise helps travelers appreciate Serengeti’s full significance beyond simple wildlife viewing.

Your Serengeti adventure awaits, offering opportunities to witness one of conservation’s greatest success stories while experiencing wildlife spectacles that inspired global conservation movements. Contact Safari Stride today to explore this legendary landscape where ancient ecosystems meet modern conservation, where natural processes continue as they have for millennia thanks to dedicated protection, and where every visitor becomes part of Serengeti’s ongoing history.

Recent Posts